Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (adhd) is a neurobehavioral disorder characterized by pervasive inattention and/or hyperactivity with impulsivity. The Centers for Disease Control (CDC) estimates some 5 million youths, ages 4-17, are currently receiving medication for the disorder.

ADHD is diagnosed approximately three times more often in boys than in girls.

Three types of ADHD have now been established:

• Predominantly Inattentive Type: It is hard for the individual to organize or finish a task, to pay attention to details, or to follow instructions or conversations. The person is easily distracted or forgets details of daily routines.

• Predominantly Hyperactive-Impulsive Type: The person fidgets and talks a lot. It is hard to sit still for long periods of time. Smaller children may run, jump or climb constantly. Someone who is impulsive may interrupt others a lot, grab things from people, or speak at inappropriate times. It is hard for the person to wait their turn or listen to directions.

• Combined Type: Symptoms of the above two types are equally predominant in the person.

Researchers and psychiatrists continue to debate (theorize) the cause of ADHD. Not everyone believes ADHD exists. A growing number of scientists and physicians have become vocal about proclaiming a group of symptoms, (AKA, typical childish behavior) a disease. Fred A. Baughman Jr., MD, author of The ADHD Fraud: How Psychiatry Makes “Patients” Out of Normal Children writes, “They made a list of the most common symptoms of emotional discomfiture of children; those which bother teachers and parents most, and in a stroke that could not be more devoid of science or Hippocratic motive—termed them a ‘disease.’ Twenty five years of research, not deserving of the term research has failed to validate ADD/ADHD as a disease.”

Regardless of the debate of whether ADHD is a disease or not, millions are being diagnosed with this condition each year. And, while we don’t know the definitive cause, theories suggest that ADHD is associated with a deficiency or malfunction in the brain chemicals known as neurotransmitters. Neurotransmitters help coordinate thought, action, moods, and over-all wellbeing. There is some evidence that people with ADHD do not produce adequate quantities of certain neurotransmitters, including dopamine, norepinephrine, and serotonin. Research further suggests that there may be fewer connections between the brain cells. And there may even be a deficit in the amount of myelin (insulating material) produced by brain cells in children with ADHD. This, of course, would further impair brain cell communication already impeded by decreased neurotransmitter levels.

Some evidence, although debated, shows that patients with ADHD demonstrate a decreased blood flow to those areas of the brain in which “self monitoring,” including impulse control, is based.

Drug Therapy

Traditional medicine advocates the use of stimulant medications for the treatment of ADHD. These medications, which include Aderrall (detroamphetamine) and Ritalin (methylphenidate), are also known as amphetamines.

Amphetamines exert their effects by binding to the monoamine transporters and increasing the extra-cellular levels of the neurotransmitters serotonin, norepinephrine and, especially, dopamine. Dopamine exerts a calming or focused effect on people who have ADHD. It enhances signaling between nerve cells that are involved in task-specific activities and also decreases stimulatory “noise.”

Spending on ADHD drugs soared from $759 million in 2000 to $3.1 billion in 2004, according to IMS Health, a pharmaceutical information and consulting firm. The United States uses approximately 90 percent of the world’s Ritalin. The International Narcotics Control Board (INCB), an agency of the World Health Organization, deplored that “10 to 12 percent of all boys between the ages six and fourteen in the United States have been diagnosed as having ADD and are being treated with Ritalin.” With 53 million children enrolled in school, probably more than 5 million are now taking stimulant drugs. The number of children on these drugs has continued to escalate. A recent study in Virginia indicated that up to 20 percent of white boys in the fifth grade were receiving stimulant drugs.

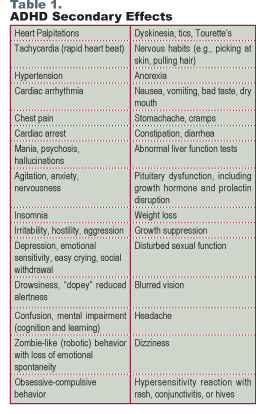

While stimulant drugs may be effective at alleviating core ADHD symptoms (such as inattention, hyperactivity, or impulsivity), it comes at a price. The potential side effects are numerous and sobering.

Amphetamines are chemically similar to cocaine. Both cause similar reactions in the brain. If we were to give cocaine to hyperactive children, instead of Ritalin, we’d most likely get similar results. Yet doing so would be criminal.

The FDA’s Canadian counterpart, Health Canada, yanked the ADHD drug Adderall XR from the market for six months in response to reports of twenty sudden deaths and twelve strokes in adults and children using the drug. Alarmingly, a recent report in the Journal of the American Medical Association has demonstrated a three-fold increase in the prescription of stimulants to 2-4 year old toddlers. Spending on drugs primarily used to treat ADHD surged 369 percent for children five years old or younger. Utilization in preschoolers was up 49 percent from 2000 to 2003. When we are reduced to using mind-numbing, health-robbing drugs on two year olds, something is definitely wrong. This whole idea of treating symptoms while poisoning the patient seems ludicrous to me.

Surely, there is a better way?

Fortunately, there is.

You know, from above, that the amphetamines work by boosting certain neurotransmitters, especially dopamine. Neurotransmitters come from the amino acids found in protein-rich foods. The neurotransmitter dopamine comes from the amino acids L-tyrosine and L-phenylalanine. Why not use L-tyrosine and or L-phenylalanine to boost dopamine? There are few side effects other than increased pulse, heart rate, and tension (rather uncommon); they work quickly within half an hour, and are often just as effective and certainly safer than amphetamines. Start with a low dose, 500mg of L-phenylalanine 30-45 minutes before breakfast (on an empty stomach) and increase as needed.

The Russian herbal compound, Rhodiola rosea has been shown to improve moods, and boost mental clarity. Research shows that it reduces fatigue and improves both physical and mental performance. Rhodiola rosea’s effects are attributed to its ability to optimize serotonin and dopamine levels.

Increased intake of omega-3 fatty acids has been shown to reduce the tendency toward hyperactivity among children with ADHD. Several studies have examined the role of essential fatty acids in ADHD, with very encouraging results. In one pilot study, researchers found that the symptoms of children with ADHD who were given omega-3 fatty acids improved on all measures. I recommend my patients supplement their diet with fish oil supplements.

Combining magnesium and vitamin B6 has shown promise for reducing symptoms of ADHD. Vitamin B6 has many functions in the body, including assisting in the synthesis of neurotransmitters and forming myelin, which protect nerves. Magnesium is also very important; it is involved in more than 300 metabolic reactions. At least three studies have demonstrated that the combination of magnesium and vitamin B6 improved behavior, decreased anxiety and aggression, and reduced hyperactivity among children with ADHD.

The mineral zinc is involved in numerous bodily processes including the production of neurotransmitters and fatty acids. Several studies have shown that individuals with ADHD are often deficient in zinc. I encourage anyone with ADHD to take a good optimal daily allowance multivitamin/mineral formula containing generous amounts of vitamin B6, zinc, and magnesium.

I find it ironic that the government spends millions of tax dollars each year advocating a “just say no to drugs” campaign. Yet, every day millions of our children are lining up at the school nursing station to receive their daily dose of speed.

Let’s get serious and stop being hypocritical about drug abuse. Telling our children that drugs are dangerous while dispensing psychoactive (mind altering) medicines to pre-school children sends the wrong message. Let’s help our children “just say no” to all dangerous drugs, including amphetamines.

Rodger Murphree, D.C., has been in private practice since 1990. He is the founder of, and past clinic director for a large integrated medical practice which was located on the campus of Brookwood Hospital in Birmingham, Alabama. He is the author of Treating and Beating Fibromyalgia and Chronic Fatigue Syndrome, Heart Disease What Your Doctor Won’t Tell You, and Treating and Beating Anxiety and Depression with Orthomolecular Medicine. He can be reached at www.treatingandbeating.com email [email protected] or 1-205-879-2383.

References

1. American Psychiatric Association: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition, Text Revision. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Association 2000.

2. Comings DE, Blum K. Reward deficiency syndrome: genetic aspects of behavioral disorders. Prog Brain Res. 2000;126:325-41.

3. Sunohara GA, Roberts W, et al. Linkage of the dopamine D4 receptor gene and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2000 Dec;39(12):1537-42.

4. Mitsis EM, Halperin JM, et al. Serotonin and aggression in children. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2000 Apr;2(2):95-101.

5. The ADHD Fraud How Psychiatry Makes “Patients” Out of Normal Children by Fred A. Baughman Jr., MD, Published by Trafford Publishing.

6. Prescription for Disaster. The Hidden Dangers in Your Medicine Cabinet. Thomas Moore. Simon and Schuster New York NY. 1998.

7. Medco Health Solutions, Inc. 2004 Drug Trend Symposium.

8. Overmeyer S, Bullmore ET, et al. Distributed grey and white matter deficits in hyperkinetic disorder: MRI evidence for anatomical abnormality in an attentional network. Psychol Med. 2001 Nov;31(8):1425-35.

9. Paule MG, Rowland AS, et al. Attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder: characteristics, interventions and models. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 2000 Sep;22(5):631-51.

10. Brown RP, Gerbarg PL, Ramazanov Z. Rhodiola rosea: a phytomedicinal overview. Herbalgram. 2002;56:40-52. Altern Med Rev 2001;6(3):293-302.

11. Spasov AA, Wikman GK, Mandrikov VB, Mironova IA, Neumoin VV. A double-blind, placebo-controlled pilot study of the stimulating and adaptogenic effect of Rhodiola rosea SHR-5 extract on the fatigue of students caused by stress during an examination period with a repeated low-dose regimen. Phytomedicine. 2000 Apr;7(2):85-9.

12. Arnold LE, DiSilvestro RA. Zinc in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2005b Aug;15(4):619-27.

13. Akhondzadeh S, Mohammadi MR, et al. Zinc sulfate as an adjunct to methylphenidate for the treatment of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in children: a double blind and randomized trial [ISRCTN64132371]. BMC Psychiatry. 2004 Apr 8;4:9.

14. Harding KL, Judah RD, et al. Outcome-based comparison of Ritalin versus food-supplement treated children with AD/HD. Altern Med Rev. 2003 Aug;8(3):319-30.

15. Joshi K, Lad S, et al. Supplementation with flax oil and vitamin C improves the outcome of Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD). Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids. 2006 Jan;74(1):17-21.

16. Nogovitsina OR, Levitina EV. Effect of MAGNE-B6 on the clinical and biochemical manifestations of the syndrome of attention deficit and hyperactivity in children [in Russian]. Eksp Klin Farmakol. 2006a Jan-Feb;69(1):74-7.Lyon MR, Cline JC, et al. Effect of the herbal extract combination Panax quinquefolium and Ginkgo biloba on attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder: a pilot study. J Psychiatry Neurosci. 2001 May;26(3):221-8.

17. Adriani W, Rea M, et al. Acetyl-L-carnitine reduces impulsive behaviour in adolescent rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2004 Nov;176(3-4):296-304.