Controversial as a pain generator and lacking the mobility of the adjacent spinal joints, the sacroiliac (SI) joint is an often overlooked target in the management of low back disorders. Because of the SI joints’ integral relationship with the hip joints, their assessments are also included to determine the hip’s relationship to any SI joint dysfunction. Subsequently, correction of SI joint dysfunction often involves adjusting the hip joints and their related muscles as well as the affected SI joint(s).

The SI Joint as a Pain Generator

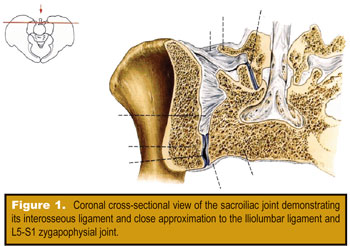

SI joint generated pain can present as low back pain, sacral pain, pelvic pain, groin pain, or gluteal pain.1 Schwarzer, et al., noted, “The sacroiliac joint is a significant source of pain in patients with chronic low back pain,” and “groin pain was found to be associated with response to sacroiliac joint block.”2 These opinions have been echoed by Duam, who said that the SI joint is an underappreciated source of low back or buttock pain.3 DonTigny also stated that the SI joint is a major factor in the etiology of idiopathic low back pain.4 Figure 1 provides a cross-sectional view of the SI joint.

SI Joint Biomechanics

The SI joint has many functions. It joins the spine to the pelvis and helps to absorb vertical forces from the spine and transmits them to the pelvis and lower extremity.5 It also allows forces to be transmitted from the extremities to the spine.6 The joint is 1-2 mm wide and decreases with age but does not fuse with normal aging. It does become stiffer and less effective as a shock absorber.7

Unlike most joints, there are no muscles acting directly across the SI joint.8 Movement does occur in the SI joint and is the result of movement of the ilia by way of the hips and trunk. The joint motion is small (2-3 degrees) and occurs in the transverse or longitudinal planes.9-11 The axes of pelvic movement passes obliquely across the pelvis. During flexion of the hip, the ipsilateral ilium glides backward and downwards. During extension, the ilium glides forward and away from the sacrum.12

SI Joint Innervation

The sacroiliac joint is lined with myelinated and unmyelinated nerve endings. They provide proprioception (position sense) and nociception (pain).20 These nerves contribute to the feed-forward mechanism of pelvis and lumbar stabilization discussed earlier. Several researchers have investigated the relationship with SI joint neurological relationships to the supporting pelvic musculature. Indahl, et al., found that SI joint dysfunction produces suprapelvic muscle hypertonicity (primarily the quadratus lumborum muscle).18 Headley emphasized, “The most common low back pain culprit (is) the quadratus lumborum (Figure 2).”19 The muscle is chronically “over-worked” and becomes tight, tender, and ultimately ineffective in its ability to provide stability to the pelvis. Thus, it has been demonstrated that the SI joint can be a pain generator, thereby affecting other areas than the joint itself. Furthermore, pain in or around the SI joint, regardless of the cause, elicits reflex inhibition of the muscles that provide stability of the joint while exciting other muscles in an attempt to provide stability and maintain normal motor activities.

The Feed-Forward Mechanism

and the SIJ

Much has been discovered and written about the feed-forward mechanism of spinal and pelvic stability. It has been found that controlling vertebral intersegmental motion through the CNS-mediated contraction of various spinal and extra-spinal muscles reduces altered and/or excessive vertebral motion that cause compression/stretch on neural structures or abnormal deformation of ligaments and pain-sensitive structures.13-15 The multifidus and transverse abdominis muscles have been implicated as two of the more important stabilization muscles. These muscles, as well as others, are “activated” by the CNS in advance of anticipated movement.

This feed-forward mechanism of stability also applies to the SI joints. Contraction of the transverse abdominis muscle has been shown to significantly increase the stability of the SI joint.16 It has been found that lumbopelvic muscles in those with SI joint pain contract differently from those without pain (both a reduced strength of contraction and speed of reaction). This includes the gluteus maximus muscle as well as the transverse abdominis (both are inhibited). In association with this alteration of the feed-forward mechanism, the biceps femoris (lateral hamstring) is activated earlier in those with SI joint pain.17 This has been referred to as an “altered motor recruitment strategy” wherein the body is recruiting the lateral hamstring to assist the inhibited gluteus maximus muscle.

SI Joint Diagnosis

The difficulty for clinicians lies in diagnosing SI joint dysfunction. In a study comparing SI Joint evaluation to gold standard SIJ arthrograms, Dreyfuss, et al., concluded that, despite all of the orthopaedic tests available, no physical examination test demonstrated worthwhile diagnostic value in SI joint diagnosis.21 More recently, Young, et al.,22 reported that the likelihood that SI joint dysfunction is the source of the pain increases markedly if three or more provocation tests are positive: 1) if the pain is unilateral, 2) if the pain is below L5 without lumbar pain, or if 3) pain increases with rising from sitting. Other than ruling out other sources of pain, imaging is generally not helpful.23

The provocative test known as the “Nachlas” test in Cipriano’s book, Photographic Manual of Regional Orthopaedic and Neurologic Tests (Williams & Wilkins), and as the “Prone Knee-Bending Test/Femoral Stretch Test/Nachlas Test/Ely Test” in Principles and Practice of Chiropractic (Appleton & Lange) has been historically used to diagnose SI joint dysfunction. This is a mechanical test that exerts movement of the SI joint by way of producing torque on the ilium through the stretch placed on the rectus femoris muscle when the prone-lying patient’s knee is flexed (Figure 3). However, Nachlas is more than just a mechanical test. The stimulation of mechanoreceptors in the SI joint, lower extremity joints, and soft tissues during its performance makes it a potent neurological test as well supplying information to the CNS that activates the feed-forward mechanism discussed previously. According to the degree of SI joint dysfunction, other reflexes, both inhibitory and excitatory, are subsequently stimulated. Both the patient’s perception of pain or discomfort and the altered

motor reflexes are considered in the diagnosis of SI joint dysfunction. Two such altered motor reflexes are the hypertonicity, and sometimes spasm, produced in the quadratus lumborum and biceps femoris muscles.

Analysis of the SI joint is not complete without assessment of the hip joints. Biomechanics authority Stuart McGill, Ph.D., said, “I am continually surprised at the number of people with back troubles who also have hip troubles.”24 The hip joint and its related muscles are intimately associated with SI joint function and, indeed, altered hip motion leads to or aggravates SI joint dysfunction. Once a diagnosis of SI joint dysfunction has been made, the SI joint and related structures, i.e., the hip joint, QL muscle, and biceps femoris muscle, are adjusted. Improvement or resolution of the factors used to diagnose SI joint dysfunction are used as the criteria that the adjustment was successful. Post-adjustment analysis, in addition, further confirms that the SI joint was dysfunctional and a pain generator.

Dr. Jim Gudgel has dual degrees as a chiropractor and physical therapist. He currently maintains a 500 PV/wk practice in Redwood Falls, MN. Dr. Chris Colloca is the CEO and Founder of Neuromechanical Innovations. Drs. Colloca and Gudgel are team instructors for Neuromechanical Innovations providing post-graduate seminars to chiropractors around the globe. For more information visit www.neuromechanical.com.

References

1. Wolfe s, et al. Worst Pills Best Pills A Consumer’s Guide to Avoiding Drug-Induced Death or Illness, Pocket Books New York, NY, 1999.

2. Ray WA, Griffin MR, Shorr RI. Adverse drug reactions and the elderly. Health Affairs 1990; 9: 114 – 122.

3. David N. Juurlink, M.D., Ph.D., et al., The Risk of Suicide with Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors in the Elderly, American Journal of Psychiatry, Vol. 163, No. 5, May 2006, pp. 813-821.

4. DonTingy, “Anterior dysfunction of the sacroiliac joint as a major factor in the etiology of idiopathic low back pain syndrome,” Physical Therapy, 1990;70

5. Dietrichs, “Anatomy of the pelvic joints,” Scandinavian Journal of Rheumatoloigy, 1991:88

7. Prather, Hunt, “Conservative management of low back pain, part I. Sacroiliac joint pain,” Dis Mon, 2004:50

8. Foley, Buschbacher, “Sacroiliac joint pain: anatomy, biomechanics, diagnosis, and treatment,” American Journal of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 2006:85.

9-11.Harrison, et al, “The sacroiliac joint: A review of anatomy and biomechanics with clinical implications,” JMPT, 1997:20; Egund, et al, “Movements in the sacroiliac joints demonstrated with roentgen stereophotogrammetry,” Acta Radiology, 1978:19; Reynolds, “Three-dimensional kinematics in the pelvic girdle,” Journal of the American Osteopathic Association, 1980:80.

12. Bogduk, “The sacroiliac joint,” in Bogduk, Clinical Anatomy of the Lumbar Spine and Sacrum,” 4th ed, Elsevier, 2005

13-15. Low Back Disorders, Stuart McGill; Therapeutic Exercise for Lumbopelvic Stabilization, Richardson, Hodges, and Hides; and Spinal Stabilization, The New Science of Back Pain, Jemmett

16. Richardson, et al “The relation between the transverse abdominis muscles, sacroiliac joint mechanics, and low back pain,” Spine, 2002:27

17. Hungerford, et al, “Evidence of altered lumbopelvic muscle recruitment in the presence of sacroiliac joint pain,” Spine, 2003:28

18. Norman, “Sacroiliac disease and its relationship to lower abdominal pain,” American Journal of Surgery, 1968;116

19. Schwarzer AC, Aprill CN, Bogduk N. “The Sacroiliac joint in chronic low back pain,” Spine 1995; 20

20. Duam,“The sacroiliac joint: an underappreciated pain generator,” American Journal of Orthopedics, 1995;24

21. DonTingy, “Anterior dysfunction of the sacroiliac joint as a major factor in the etiology of idiopathic low back pain syndrome,” Physical Therapy, 1990;70

22. Dietrichs, “Anatomy of the pelvic joints,” Scandinavian Journal of Rheumatoloigy, 1991:88

23. Bogduk, “The sacroiliac joint,” Clinical Anatomy of the Lumbar Spine and Sacrum, 3rd edition, Churchill Livingstone, 1997

24. Prather, Hunt, “Conservative management of low back pain, part I. Sacroiliac joint pain,” Dis Mon, 2004:50

25. Foley, Buschbacher, “Sacroiliac joint pain: anatomy, biomechanics, diagnosis, and treatment,” American Journal of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 2006:85

26-28. Harrison, et al, “The sacroiliac joint: A review of anatomy and biomechanics with clinical implications,” JMPT, 1997:20; Egund, et al, “Movements in the sacroiliac joints demonstrated with roentgen stereophotogrammetry,” Acta Radiology, 1978:19; Reynolds, “Three-dimensional kinematics in the pelvic girdle,” Journal of the American Osteopathic Association, 1980:80

29. Bogduk, “The sacroiliac joint,” in Bogduk, Clinical Anatomy of the Lumbar Spine and Sacrum,” 4th ed, Elsevier, 2005

30-32. Low Back Disorders, Stuart McGill; Therapeutic Exercise for Lumbopelvic Stabilization, Richardson, Hodges, and Hides; and Spinal Stabilization, The New Science of Back Pain, Jemmett

33. Richardson, et al “The relation between the transverse abdominis muscles, sacroiliac joint mechanics, and low back pain,” Spine, 2002:27

34. Hungerford, et al, “Evidence of altered lumbopelvic muscle recruitment in the presence of sacroiliac joint pain,” Spine, 2003:28

35. “Sacroiliac joint involvement in activation of porcine spinal and gluteal musculature,” Journal of Spinal Discord, 1999:12

36. Headley, When Movement Hurts, 1997

37. Wyke, “Receptor systems in lumbosacral tissues in relation to the production of low back pain,” American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons Symposium on Idiopathic Low Back Pain, Mosby, 1982

38. Dreyfuss,“The value of medical history and physical examination in diagnosing sacroiliac joint pain,” Spine, 1996;21

39. Young, et al, “Correlation of clinical examination characteristics with three sources of chronic low back pain,” Spine, 2003;3

40. Elgafy, et al, “Computed tomography findings in patients with sacroiliac pain,” Clinical Orthopedics Related Research, 2001;382