In my experience, there is a general lack of appreciation of both the need for radiographic views of the thoracic spine and the influence of the thoracic spine on whole body alignment and health potential. It is for these reasons that I offer this particular series of articles introducing my thoughts on the thoracic kyphosis to readership of the The American Chiropractor.

Radiographic Measurements

Radiographic Measurements

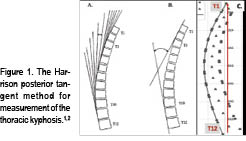

In the early 1980’s, my father–Dr. Donald Harrison1–developed specific radiographic measurement methods to assess the magnitude and distribution of the thoracic kyphosis. These measurements were termed “the Harrison Posterior Tangents.” Later (2001), we investigated the reliability of these kyphosis measures and identified small standard errors of measurement and good to excellent intra- and inter-examiner reliability.2 Figure 1 shows the Harrison posterior tangent method.

Average Thoracic Kyphosis Angles

Several studies have reported “normal” values of thoracic kyphosis in a wide range of age groups.3-5 The density of the upper ribcage, in the coronal plane, can cause an inability to accurately identify and measure the vertebral segments T1-T4. Because of this, various authors have utilized different vertebral levels when measuring the thoracic kyphosis and a large range of values for kyphosis (20° to 50°) has been reported.3,4

Problematically, some of this normal subject data is contaminated with subjects that should not be considered healthy. For one example, Fon, et al.,5 presented thoracic kyphosis measurement in 316 “normal subjects” aged 2-77 yrs. Their definition of normal was: “…while the general status of some of these patients was not optimal, it was assumed that the patients were sufficiently fit to be ambulatory….”

Problematically, some of this normal subject data is contaminated with subjects that should not be considered healthy. For one example, Fon, et al.,5 presented thoracic kyphosis measurement in 316 “normal subjects” aged 2-77 yrs. Their definition of normal was: “…while the general status of some of these patients was not optimal, it was assumed that the patients were sufficiently fit to be ambulatory….”

Beginning in 2001, my colleagues and I proposed a more narrow distribution of thoracic kyphosis values as normal: average values for T3-T10 posterior tangents = 33°-37°.3,4 Part of our reasoning for a narrower range of normal thoracic kyphosis was based on a study done in 2002.6 Here, we identified that translated postures of the ribcage relative to the pelvis in the sagittal plane can have a strong influence on the magnitude of thoracic kyphosis. Specifically, a total change of 26° in thoracic kyphosis was found for maximum posterior translation of the ribcage to maximum anterior translation in normal subjects. (See Figure 2.)

:dropcap_open:Poorer health status, increased disability, and increased pain levels in patients with anterior trunk postures.:quoteleft_close:

Furthermore, biomechanical models have predicted large increases in extensor muscle loads and consequent increased compression and shear loads on the thoraco-lumbar spine discs when sagittal trunk translation is present.7,8 These high compressive and shear loads may produce pain and initiate or contribute to a degenerative remodeling response in the disc. In fact, Glassman, et al.9, identified poorer health status, increased disability, and increased pain levels in patients with anterior trunk postures.

The issues associated with sagittal plane ribcage translation prompted my colleagues and I4 to present thoracic kyphosis data from a group of 50 normal subjects whose sagittal translation was within 1 standard deviation of the mean (neutral alignment). This data is presented in Table 1.

Average & Ideal Thoracic Kyphosis Models

Average & Ideal Thoracic Kyphosis Models

Harrison and colleagues3 presented average geometric models of the thoracic kyphosis (T1-T12, T2-T11, and T3-T10 segments were modelled) as a segment of an ellipse using pooled data from 80 normal subjects’ lateral thoracic radiographs. Figure 3 shows the average elliptical model of the segments T1-T12.3

Harrison and colleagues3 presented average geometric models of the thoracic kyphosis (T1-T12, T2-T11, and T3-T10 segments were modelled) as a segment of an ellipse using pooled data from 80 normal subjects’ lateral thoracic radiographs. Figure 3 shows the average elliptical model of the segments T1-T12.3

Harrison, et al.4 followed this paper with an optimized elliptical model of thoracic kyphosis based in part on data from 50 optimized normal subjects. Since the thoracic vertebral bodies increase in size considerably from T1 to T12, a uniformly increasing model was derived for disc and vertebral body sizes using anatomical literature. We found that the major axis of the ellipse (long axis of an oval) is parallel to the posterior body margin of T12, whereas the minor axis of the ellipse (short axis of the oval) passed through the superior  endplate of T12. The minor axis to major axis ratio was computed to be 0.69.4 Figure 4 shows this optimized elliptical model in a template form that can be used for any height of a patient.

endplate of T12. The minor axis to major axis ratio was computed to be 0.69.4 Figure 4 shows this optimized elliptical model in a template form that can be used for any height of a patient.

In the more recent literature, investigators have begun to develop individual subject optimized geometric sagittal plane curve models for thoracic kyphosis.10-12 There are certain anatomic variables that have been shown to have a moderate influence on sagittal plane curvature. When these anatomic variables are outside of normal tolerances, a change in sagittal curvature can result. This information will be detailed in Part 2 of this series.

Summary

Chiropractic has a long history of identifying and attempting to restore normal alignment to the spine, where abnormal alignment is specifically referred to as the mechanical component of vertebral subluxation. The key is to fully understand when the modelling and alignment data presented herein is useful in differentiating a subluxated thoracic spine from a normal spine and how to modify the data and intervene in specific patient situations. Till next time.

Dr. Deed will be presenting a comprehensive, contemporary review of this topic at the upcoming 33rd CBP Annual Conference on Sept. 23-25th, in Phoenix, AZ.

References

• Harrison DD. Spinal Biomechanics: A Chiropractic Perspective. National Library of Medicine #WE 725 4318C, 1982-97.

• Harrison DE, Cailliet R, Harrison DD, Janik TJ, Holland B. Centroid, Cobb or Harrison Posterior Tangents: Which to Choose for Analysis of Thoracic Kyphosis? Spine 2001; 26(11): E227-E234.

• Harrison DE, Janik TJ, Harrison DD, Cailliet R, Harmon S. Can the thoracic kyphosis be modeled with a simple geometric Shape? The results of circular and elliptical modeling in 80 asymptomatic subjects. J Spinal Disord Tech 2002; 15(3): 213-220.

• Harrison DD, Harrison DE, Janik TJ, Cailliet R, Haas JW. Do alterations in vertebral and disc dimensions affect an elliptical model of the thoracic kyphosis? Spine 2003;463-469.

• Fon GT, Pitt MJ, Thies AC Jr. Thoracic

• kyphosis: range in normal subjects. AJR 1980;134(5):979-83.

• Harrison DE, et al. How Do Anterior/Posterior Translations of the Thoracic Cage Affect the Sagittal Lumbar Spine, Pelvic Tilt, and Thoracic Kyphosis? Eur Spine J 2002;11:287-293.

• Harrison DE, Colloca CJ, Keller TS, Harrison DD, Janik TJ. Anterior thoracic posture increases thoracolumbar disc loading. Eur Spine J 2005; 14:234-242.

• Kiefer A, Shirazi-Adl A, Parnianpour M. Synergy of the human spine in neutral postures. Eur Spine J 1998; 7:471-479.

• Glassman SD, Bridwell K, Dimar JR, Horton W, Berven S, Schwab F. The impact of positive sagittal balance in adult spinal deformity. Spine 2005;30:2024-2029.

• Berthonnaud E, et al. Analysis of the sagittal balance of the spine and pelvis using shape and orientation parameters. J Spinal Disorders & Techniques 2005;18(1):40-47.

• Vaz G, Roussouly P, Berthonnaud E, Dimnet J. Sagittal morphology and equilibrium of pelvis and spine. Eur Spine J 2002; 11(1):80-87.

• Vialle R, Levassor N, Rillardon L, Templier A, Skalli W, Guigui P. Radiographic analysis of the sagittal alignment and balance of the spine in asymptomatic subjects. J Bone Joint Surgery 2005;87Am:260-267.

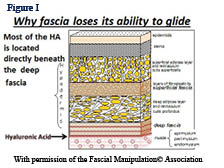

So what is this white stuff covering everything in our body? The infinite wisdom of nature would not just bother to cover our whole body with white stuff that solely functions as a covering. Probably the most important function of fascia is that it is a sensory organ loaded with mechanoreceptors and proprioceptors. Every single muscle fiber in our body is covered by fascia. Many muscles originate and insert into fascia, not to mention the intramuscular fascia. Whenever a muscle is stretched or contracts the surrounding fascia must be stretched. The muscle spindle cell should be called the fascial spindle cell since they are located in the fascia. As soon as a muscle is activated, spindle cells immediately report back to the CNS the status of the muscle such as its tone, position and movement. In order for this mechanism to work properly, fascia must have a normal viscosity whereby the spindle cells, Paccini and Ruffini receptors can be normally stretched. What if fascia is restricted and unable to glide over the muscle or within the muscle during muscle activity? Alteration of fascial movement due to increased viscosity (density) of the fascia would lessen the normal feedback to the CNS and muscle incoordination would occur. A recent e-mail exchange with Siegfried Mense, MD a leading expert on muscle pain and neurophysiology was asked if fascial adhesions would have an adverse affect on spindle cells. He stated: “Structural disorders of the fascia can surely distort the information sent by the spindles to the CNS and thus can interfere with a proper coordinated movement”. Antonio Stecco, MD has many ultrasound studies showing the correlation between stiff thickened fascia and diminished sliding being responsible for neck pain³. Helen Langevin, MD did an ultrasound study showing that people with chronic or recurrent low back pain compared to no low back pain had 25% greater perimuscular thickness and echogenicity4.

So what is this white stuff covering everything in our body? The infinite wisdom of nature would not just bother to cover our whole body with white stuff that solely functions as a covering. Probably the most important function of fascia is that it is a sensory organ loaded with mechanoreceptors and proprioceptors. Every single muscle fiber in our body is covered by fascia. Many muscles originate and insert into fascia, not to mention the intramuscular fascia. Whenever a muscle is stretched or contracts the surrounding fascia must be stretched. The muscle spindle cell should be called the fascial spindle cell since they are located in the fascia. As soon as a muscle is activated, spindle cells immediately report back to the CNS the status of the muscle such as its tone, position and movement. In order for this mechanism to work properly, fascia must have a normal viscosity whereby the spindle cells, Paccini and Ruffini receptors can be normally stretched. What if fascia is restricted and unable to glide over the muscle or within the muscle during muscle activity? Alteration of fascial movement due to increased viscosity (density) of the fascia would lessen the normal feedback to the CNS and muscle incoordination would occur. A recent e-mail exchange with Siegfried Mense, MD a leading expert on muscle pain and neurophysiology was asked if fascial adhesions would have an adverse affect on spindle cells. He stated: “Structural disorders of the fascia can surely distort the information sent by the spindles to the CNS and thus can interfere with a proper coordinated movement”. Antonio Stecco, MD has many ultrasound studies showing the correlation between stiff thickened fascia and diminished sliding being responsible for neck pain³. Helen Langevin, MD did an ultrasound study showing that people with chronic or recurrent low back pain compared to no low back pain had 25% greater perimuscular thickness and echogenicity4.  How does FM work to free the fascia and how does it differ from all other soft tissue methods. Over the years Luigi Stecco realized that there were particular areas in the muscles and retinacula around joints that when released solved many musculoskeletal problems. Stecco found that muscles work in groups and that we could consider these groups in terms of myofascial units (MFU). Luigi thought that if there are muscle fibers contracting together as a group, then for a particular direction some of the fibers will be tensioning their overlying and intra fascia when they contract and somewhere there will be a mathematical point where the vector forces will converge in a given movement pattern. In other words specific motor units will converge on a point in the deep fascia for a specific direction. He called these points centers of coordination (CCs) which were located in a myofascial unit. A MFU is defined as particular motor units activating monoarticular and biarticular muscle fibers, their deep fascia and the joint they move in one direction on one plane (Figure II.) The CCs are often in the belly of the muscle where most of the fascial spindle cells are located. These areas are often proximal to the painful area and the patient is often surprised that they are tender. But if these points are involved they will be palpated as densified, tender areas. Luigi has correlated functional testing (contraction or passive stretching of the area) with these points. For example anterior forearm pain could be created by palpating and treating anterior points not necessarily on the forearm, see figure II. Figure II represents 4 MFU making up an anterior sequence. Fascia is stretched by a muscle due to its fascial expansions and this tension is transmitted during a forward movement of the arm. During forward movement of the whole arm the contraction of the clavicular fibers of the pectoralis major will stretch the anterior region of the brachial fascia due to its myofascical expansion. The simultaneous contraction of the biceps muscle will stretch the anterior region of the antebrachial fascia by way of the bicipital aponeurosis (lacertus fibrosis) as the palmaris longus pulls on the flexor retinaculum, palmar aponeurosis and thenar fascia. The anatomical fascial/muscle connection for example has been shown in anatomical dissection by the Steccos 6. While this forward movement is occurring the proprioceptors within the fasciae are activated permittingthe perception of the motor direction.

How does FM work to free the fascia and how does it differ from all other soft tissue methods. Over the years Luigi Stecco realized that there were particular areas in the muscles and retinacula around joints that when released solved many musculoskeletal problems. Stecco found that muscles work in groups and that we could consider these groups in terms of myofascial units (MFU). Luigi thought that if there are muscle fibers contracting together as a group, then for a particular direction some of the fibers will be tensioning their overlying and intra fascia when they contract and somewhere there will be a mathematical point where the vector forces will converge in a given movement pattern. In other words specific motor units will converge on a point in the deep fascia for a specific direction. He called these points centers of coordination (CCs) which were located in a myofascial unit. A MFU is defined as particular motor units activating monoarticular and biarticular muscle fibers, their deep fascia and the joint they move in one direction on one plane (Figure II.) The CCs are often in the belly of the muscle where most of the fascial spindle cells are located. These areas are often proximal to the painful area and the patient is often surprised that they are tender. But if these points are involved they will be palpated as densified, tender areas. Luigi has correlated functional testing (contraction or passive stretching of the area) with these points. For example anterior forearm pain could be created by palpating and treating anterior points not necessarily on the forearm, see figure II. Figure II represents 4 MFU making up an anterior sequence. Fascia is stretched by a muscle due to its fascial expansions and this tension is transmitted during a forward movement of the arm. During forward movement of the whole arm the contraction of the clavicular fibers of the pectoralis major will stretch the anterior region of the brachial fascia due to its myofascical expansion. The simultaneous contraction of the biceps muscle will stretch the anterior region of the antebrachial fascia by way of the bicipital aponeurosis (lacertus fibrosis) as the palmaris longus pulls on the flexor retinaculum, palmar aponeurosis and thenar fascia. The anatomical fascial/muscle connection for example has been shown in anatomical dissection by the Steccos 6. While this forward movement is occurring the proprioceptors within the fasciae are activated permittingthe perception of the motor direction.

In January 2006, I had the great honour of being chosen to be featured on the cover of The American Chiropractor Magazine. The associated article was about a superlatively effective treatment concept which I refer to as multimodal therapeutic “neurosummation®”. This is the fundamental basis of the treatment system, called “Trigenics”, which is designed to neurologically reprogram and correct muscle pull pattern imbalances through sensorimotor, neural re-regulation. The originality of the Trigenics® method of treatment was that it incorporated the concept of simultaneous, instrument or manually applied, multiple source (multimodal) neural stimulation as an evidence-based / supportive clinical approach for enhanced therapeutic outcome. It was designed as a system of highly advanced neurogenic treatment for patients with musculoskeletal disorders and pain syndromes as well as a method of preventing injuries and augmenting athletic performance.

In January 2006, I had the great honour of being chosen to be featured on the cover of The American Chiropractor Magazine. The associated article was about a superlatively effective treatment concept which I refer to as multimodal therapeutic “neurosummation®”. This is the fundamental basis of the treatment system, called “Trigenics”, which is designed to neurologically reprogram and correct muscle pull pattern imbalances through sensorimotor, neural re-regulation. The originality of the Trigenics® method of treatment was that it incorporated the concept of simultaneous, instrument or manually applied, multiple source (multimodal) neural stimulation as an evidence-based / supportive clinical approach for enhanced therapeutic outcome. It was designed as a system of highly advanced neurogenic treatment for patients with musculoskeletal disorders and pain syndromes as well as a method of preventing injuries and augmenting athletic performance. Initially, Trigenics® was, considered to be either leading edge or abstract in that it put the initial primary focus of therapy on augmentative correction of aberrant sensorimotor control neurology rather than the aberrant biomechanics found in interosseous dyskinesia and/or soft tissue adhesions with myofascial glide/tightness dysfunction.I can well remember traveling avidly on the lecture circuit for years in the early 2000’s providing presentations for schools and organizations like the OCA, ACA, FCA, American Sports Council, the ACBSP and even Parker Seminar throughout North America, vigorously espousing the need to first address aberrant muscle neurology when the big buzz was then still all about excellent soft tissue myofascial adhesion release techniques like “active release technique” (ART) or “myobrasion”® techniques like “Graston”.

Initially, Trigenics® was, considered to be either leading edge or abstract in that it put the initial primary focus of therapy on augmentative correction of aberrant sensorimotor control neurology rather than the aberrant biomechanics found in interosseous dyskinesia and/or soft tissue adhesions with myofascial glide/tightness dysfunction.I can well remember traveling avidly on the lecture circuit for years in the early 2000’s providing presentations for schools and organizations like the OCA, ACA, FCA, American Sports Council, the ACBSP and even Parker Seminar throughout North America, vigorously espousing the need to first address aberrant muscle neurology when the big buzz was then still all about excellent soft tissue myofascial adhesion release techniques like “active release technique” (ART) or “myobrasion”® techniques like “Graston”.

The brain’s ability to change its neural network connections and behavior in response to new information, sensory stimulation, development, damage or dysfunction is called “neuroplasticity.” However, up until the year 2002, healthcare professionals were taught that we are born with all the brain cells we will ever have, they will die off as we get older, and we will never create any new ones. It has now been confirmed that we are born and die with millions of unused and unformed stem-cells in our brains that can be used to make new brain cells as we need them throughout our entire life.

The brain’s ability to change its neural network connections and behavior in response to new information, sensory stimulation, development, damage or dysfunction is called “neuroplasticity.” However, up until the year 2002, healthcare professionals were taught that we are born with all the brain cells we will ever have, they will die off as we get older, and we will never create any new ones. It has now been confirmed that we are born and die with millions of unused and unformed stem-cells in our brains that can be used to make new brain cells as we need them throughout our entire life.

:dropcap_open:W:dropcap_close:ithout question the main cause of elite athletes not attaining their goals is injuries. Debilitating injury to muscles or tendons being the culprit. Much has been discovered in recent years relating to the imbalance mechanisms of aberrant and imbalanced pull pattern muscule function. (Janda, Lewit, Leibenson, et al, etc.) Creating an afferent barrage for a neurosummation effect using the Trigenics multimodal procedures provides an advanced neurologically-based assessment system and a neurologically enhanced treatment system to correct functional motor control imbalances for rapid repair and prevention of injuries as well as augmentation of training outcome.

:dropcap_open:W:dropcap_close:ithout question the main cause of elite athletes not attaining their goals is injuries. Debilitating injury to muscles or tendons being the culprit. Much has been discovered in recent years relating to the imbalance mechanisms of aberrant and imbalanced pull pattern muscule function. (Janda, Lewit, Leibenson, et al, etc.) Creating an afferent barrage for a neurosummation effect using the Trigenics multimodal procedures provides an advanced neurologically-based assessment system and a neurologically enhanced treatment system to correct functional motor control imbalances for rapid repair and prevention of injuries as well as augmentation of training outcome.

Problematically, some of this normal subject data is contaminated with subjects that should not be considered healthy. For one example, Fon, et al.,5 presented thoracic kyphosis measurement in 316 “normal subjects” aged 2-77 yrs. Their definition of normal was: “…while the general status of some of these patients was not optimal, it was assumed that the patients were sufficiently fit to be ambulatory….”

Problematically, some of this normal subject data is contaminated with subjects that should not be considered healthy. For one example, Fon, et al.,5 presented thoracic kyphosis measurement in 316 “normal subjects” aged 2-77 yrs. Their definition of normal was: “…while the general status of some of these patients was not optimal, it was assumed that the patients were sufficiently fit to be ambulatory….”

Harrison and colleagues3 presented average geometric models of the thoracic kyphosis (T1-T12, T2-T11, and T3-T10 segments were modelled) as a segment of an ellipse using pooled data from 80 normal subjects’ lateral thoracic radiographs. Figure 3 shows the average elliptical model of the segments T1-T12.3

Harrison and colleagues3 presented average geometric models of the thoracic kyphosis (T1-T12, T2-T11, and T3-T10 segments were modelled) as a segment of an ellipse using pooled data from 80 normal subjects’ lateral thoracic radiographs. Figure 3 shows the average elliptical model of the segments T1-T12.3 endplate of T12. The minor axis to major axis ratio was computed to be 0.69.4 Figure 4 shows this optimized elliptical model in a template form that can be used for any height of a patient.

endplate of T12. The minor axis to major axis ratio was computed to be 0.69.4 Figure 4 shows this optimized elliptical model in a template form that can be used for any height of a patient.

Contra-indications for the Compression-Extension Wedge:

Contra-indications for the Compression-Extension Wedge: